Background: Neuropsychiatric lupus (NPSLE) affects the central (CNS) and peripheral (PNS) nervous system. Complications in the CNS associated with SLE include behavioral and cognitive dysfunction, and the use of animal models becomes indispensable to better understand NPSLE [1]. Pristane-induced lupus (PIL) presents multiple classification criteria of SLE, but the neuropsychiatric manifestations are poorly studied in this model [2]. In this context, vitamin D (VitD) has been studied for its immunomodulatory and neuroprotective effects in autoimmune diseases [3].

Objectives: To describe neuropsychiatric manifestations in the pristane-induced lupus model and to evaluate the effect of VitD supplementation on behavior.

Methods: Seventy-six BALB/c mice were divided into 3 groups: CO (control, n=24), PIL (induced at T0 with 500μL of pristane intraperitoneally, n=28), and VD (PIL with VitD supplementation [2ug/kg] every two days subcutaneously, n=28). Depressive-like behavior was assessed using the forced-swim test, measuring swimming and immobility time. Anxious-like behavior was measured with the elevated plus maze test, analyzing number of entries into and time spent in the open arms. Memory was evaluated through the Barnes maze, assessing escape latency time, number of errors, and hits on the escape/target orifice for short-term memory and long-term memory. Statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s were used. P value was considered ≤0.05.

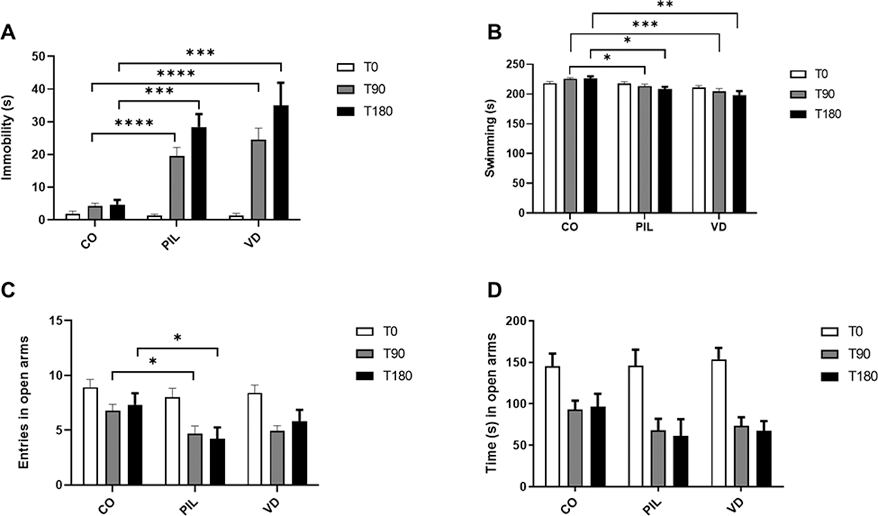

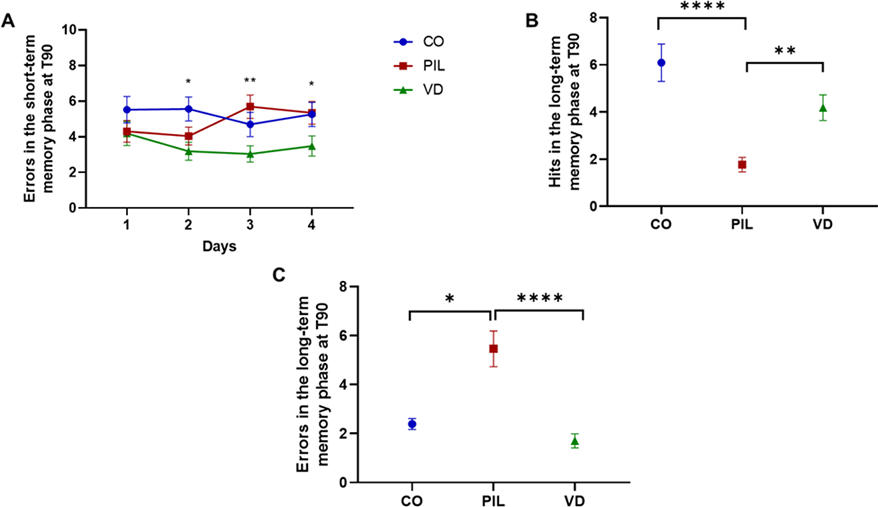

Results: Compared with CO, both PIL and VD groups showed longer immobility time in the forced-swim test, at T90 (COvsPIL, p<0.0001; COvsVD, p<0.0001) and at T180 (COvsPIL, p<0.001; COvsVD, p<0.001) (Figure 1A), as well as a reduction in swim activity at T90 (COvsPIL, p<0.05; COvsVD, p<0.001) and at T180 (COvsPIL, p<0.05; COvsVD, p<0.01) (Figure 1B). There was a reduction in the number of entries that the animals in the PIL group sought to explore the open arms in the elevated plus maze, compared with the CO group (T90: COvsPIL, p=0.05; T180: COvsPIL, p<0.05) (Figure 1C). There was no difference in the time spent in the open arms (Figure 1D). In the Barnes maze, VD had a lower number of errors compared with the PIL group for short-term memory at T90 (PILvsVD, p<0.01) (Figure 2A). For long-term memory, PIL had a lower number of hits (PILvsCO, p<0.0001; PILvsVD, p<0.01) and a higher number of errors (COvsPIL, p<0.05; PILvsVD, p<0.0001) compared with CO and VD groups at T90 (Figure 2B/C). There was no statistically significant difference in escape latency at T90 or in the other parameters evaluated at T180.

Data from forced-swim and elevated plus maze tests: A) Time (in seconds) mice stood immobile during the forced-swim test. B) Time (s) mice remained swimming during the forced-swim test. C) Number of open armies’ entries in the elevated plus maze. D) Time (s) mice remained in the open armies of the maze. *p≤0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001; CO: control; PIL: pristane-induced lupus; VD: pristane-induced lupus + vitamin D.

Data from Barnes maze test for short (STM) and long-term memory (LTM): A) Times the animal explored an orifice other than the target (STM at T90); B) Times the animal explored the target orifice (LTM at T90); C) Times the animal explored an orifice other than the target (LTM at T90). *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ****p<0.0001; CO: control; PIL: pristane-induced lupus; VD: pristane-induced lupus + vitamin D.

Conclusion: The PIL model exhibited neuropsychiatric manifestations, showing symptoms consistent with anxiety, depression, and memory deficit. While VitD supplementation did not impact anxious and depressive-like behavior, it demonstrated a potential positive effect on memory parameters.

REFERENCES: [1] Vo A et al. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014 Aug;34(8):1315-20. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.85

[2] Freitas EC, de Oliveira MS, Monticielo OA. Clin Rheumatol. 2017 Nov;36(11):2403-2414. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3811-6

[3] Karnopp TE et al. Adv Rheumatol. 2024 Jan 2;64(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s42358-023-00344-w

Acknowledgements: Douglas dos Santos Soares (Laboratório de Pesquisa Cardiovascular at HCPA); Unidade de Experimentação Animal (HCPA); Diretoria de Pesquisa (HCPA); and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Disclosure of Interests: None declared.