Background: European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) task force (TF) requires participation of at least three representative members - one health professional in Rheumatology (HPR) and two patient research partners (PRP), and two junior members from the Emerging EULAR Network (EMEUNET). Incorporating members with different perspectives has been associated with better patient care. Nevertheless, the participation of the junior or representative members in a TF has never been evaluated.

Objectives: Our objective was to evaluate their preparation and their participation in the TF as compared to other traditional members (i.e., convenors, regular TF members, methodologists and fellows).

Methods: An online survey was sent to previous EULAR TF participants comprising 49 questions in 3 categories: i ) Demographics and TF information, ii ) TF preparation, iii ) TF participation. Multiple-choices, open-ended and rating scale items (0 being fully disagree to 100 being fully agree) were used to evaluate the preparation and participation among participants in the TF. Comparisons were performed using Chi 2 , Wilcoxon test, or T-test for paired data, where appropriate.

Results: This study included 77 respondents from 24 countries, 48 (62%) were women. Their ages were categorized as: 26-35 (19%), 36-45 (29%), 46-55 (18%), and >55 (34%). Forty-six (60%) participated as a junior or a representative member (23/77 as EMEUNET, 10/77 as HPR, and 14/77 as PRP), 13/77 (17%) as convenor, 7/77 (9%) as methodologist, 20/77 (26%) as fellows and 50/77 (65%) as regular TF members.

Junior and representative members reported less clarity about their roles compared to traditional members (80 [IQR 66, 90] vs. 88.5 [IQR 72.8, 99], p = 0.048, on a scale from 0=absolutely unclear to 100=absolutely clear).

Most junior and representative members (10/14, 71%) felt unprepared for their first TF. Among participants who felt unprepared for their first TF 14/74 (19%), 10 were junior or representative members (4 junior members, 3 HPR and 3 PRP). Participants who felt prepared (39/60, 65%) had read the Standard Operating Procedures before the TF more often compared to those who did not feel prepared (5/14, 36%), p=0.07.

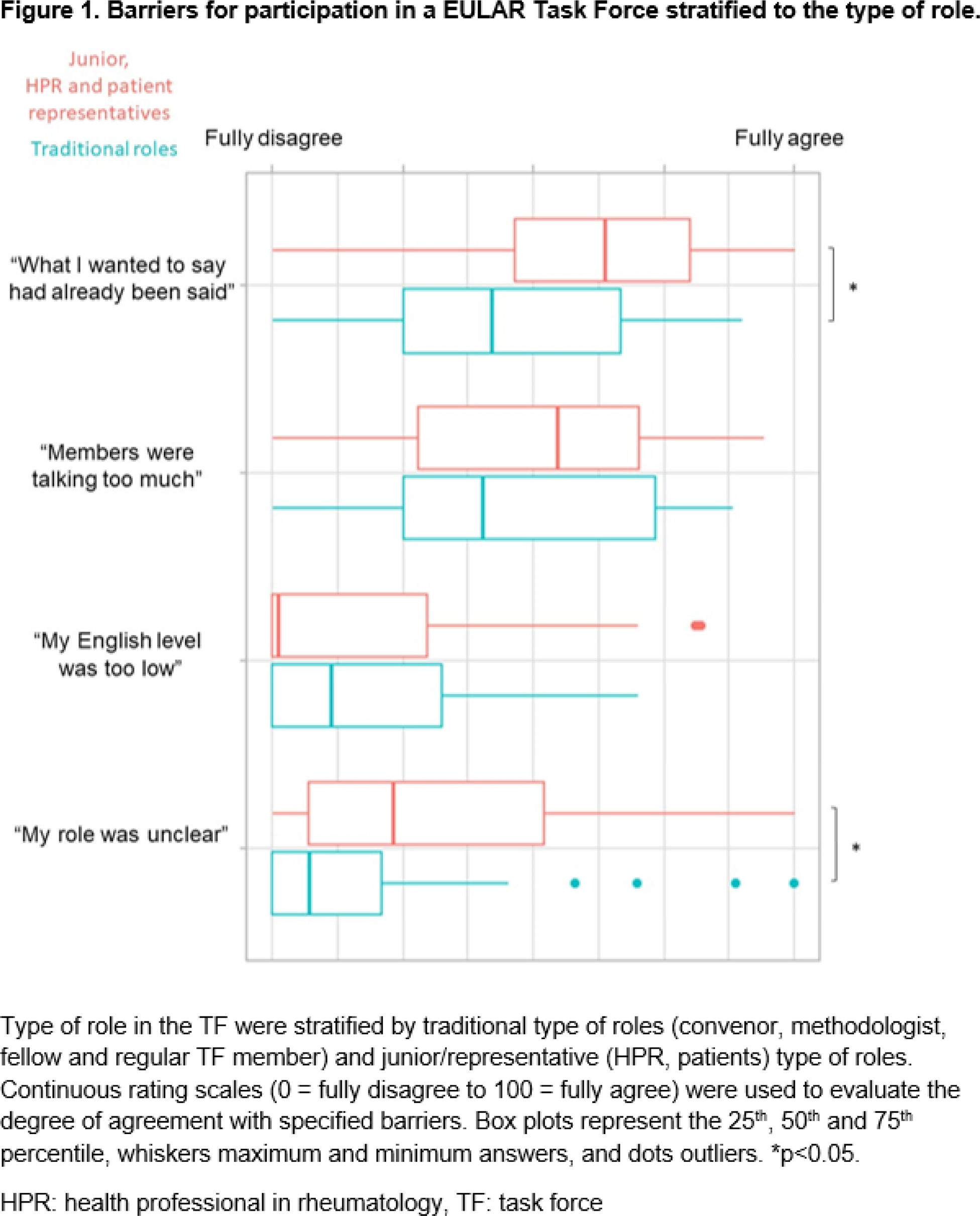

Figure 1 presents barriers to participation stratified by the TF role. Compared to traditional members, junior and representative members were more likely to fear “looking stupid” (30.0%, [IQR 15.0, 57.0] vs. 10.0% [IQR 1.0, 51.0], p=0.04) and “not being expert enough”, (50.0%, [IQR 17.0, 70.0] vs. 20.0% [IQR 3.8.0, 50.5], p=0.07). No difference was observed for “feeling unsafe” (7% [IQR 1, 34] vs. 11.0% [IQR 0.0, 29.0], p>0.99). Ten participants reported that they had felt unwelcomed (4 patients, 3 HPR, 1 junior and 2 regular TF members).

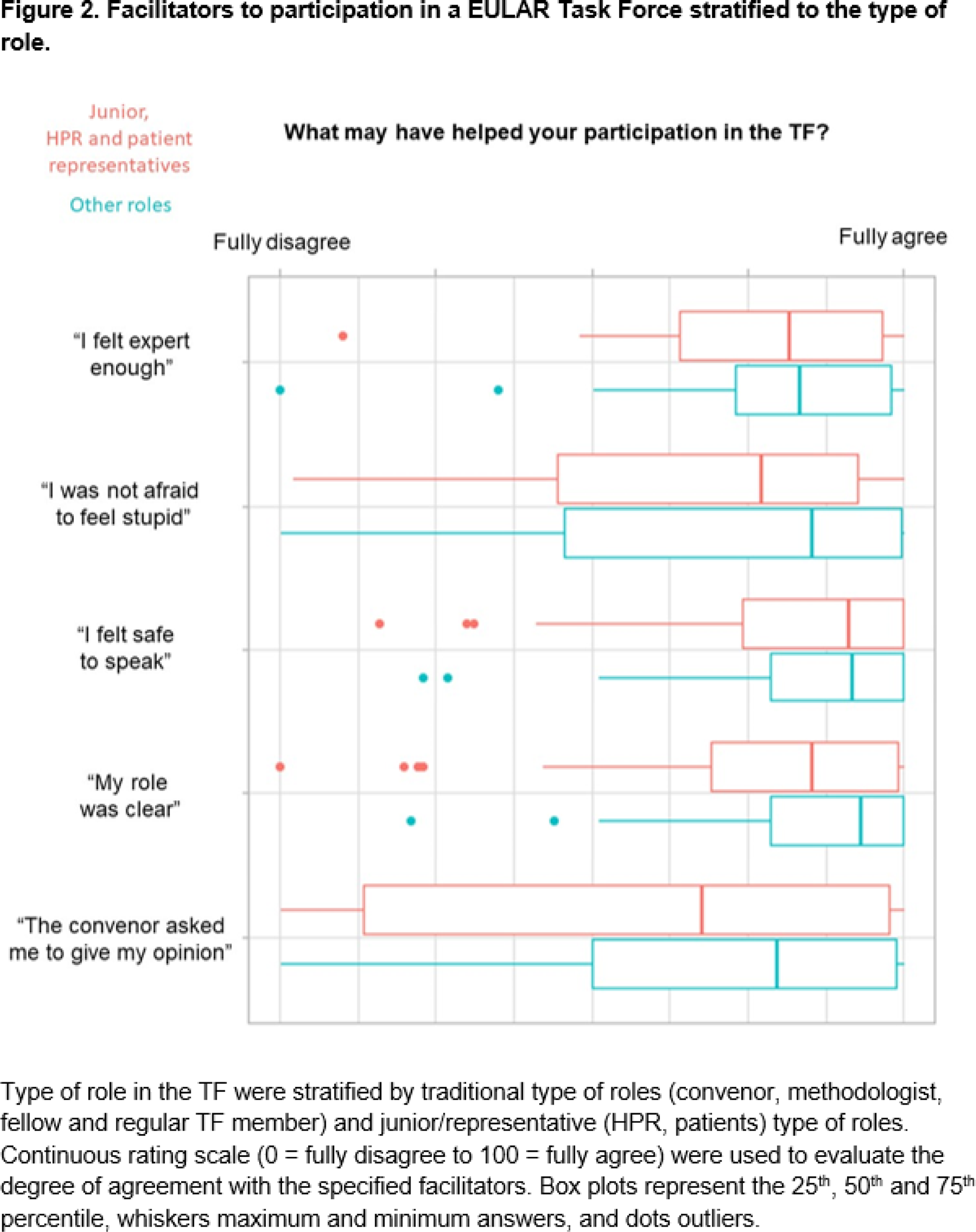

Though not statistically significant, junior and representative members were more likely to feel that participation was facilitated when opinions were “directly asked by the convenor” (79.5% agree, [IQR 50.0, 98.8] vs, 67.5%, [IQR 13.5 – 97.8], p=0.15), Figure 2. When asked which member helped their participation the most, 15/28 (54%) junior and representative members answered “the convenor”, compared to 22/31 (71%) for other members, p=0.17). Interaction was facilitated by experience, expertise and preparation (54%), being supported or specifically spoken to by the convenor (42%), and perceiving to have a clear role (12%).

Convenors and methodologists were more likely than other TF members to attribute responsibility for active participation in meetings to the convenor 66, [IQR 58.5, 73] vs. 51, [IQR 50, 60.8] for (p= 0.01).

Conclusion: Juniors, patients and HPR members faced specific barriers to active participation (uncertain role, inadequate preparation, and difficulties for engaging) which differed from those experienced by traditional TF members. Our study underscores the need for both better participant preparation and stronger convenor support. Furthermore, we suggest a systematic evaluation after each TF to inform ongoing adjustments.

REFERENCES: NIL.

Acknowledgements: NIL.

Disclosure of Interests: None declared.