Background: Chronic neck or back pain (spinal pain) is prevalent and among the leading causes of disability worldwide [1]. It often coexists with other chronic conditions, increasing both individual and societal burdens [2]. The coexistence of two or more chronic conditions is often termed multimorbidity [3], and individuals with multimorbidity are frequently underrepresented in research due to exclusion from clinical trials [4]. As multimorbidity is associated with greater personal burdens, poorer health, and reduced quality of life [3], these individuals may be less likely to participate in studies, introducing non-response bias. This occurs when those who do not respond differ in important ways from those who do, potentially skewing research findings [5]. Successive wave analyses, a method involving multiple reminders to non-respondents, can help assess non-response bias by comparing characteristics of later responders with those of initial responders [6]. It is unclear, however, whether self-reported factors related to multimorbidity, such as treatment burden and health status, contribute to this bias.

Objectives: To investigate whether self-reported treatment burden, health-related quality of life, health status, and the number of comorbidities, are associated with non-response bias in patients with chronic spinal pain.

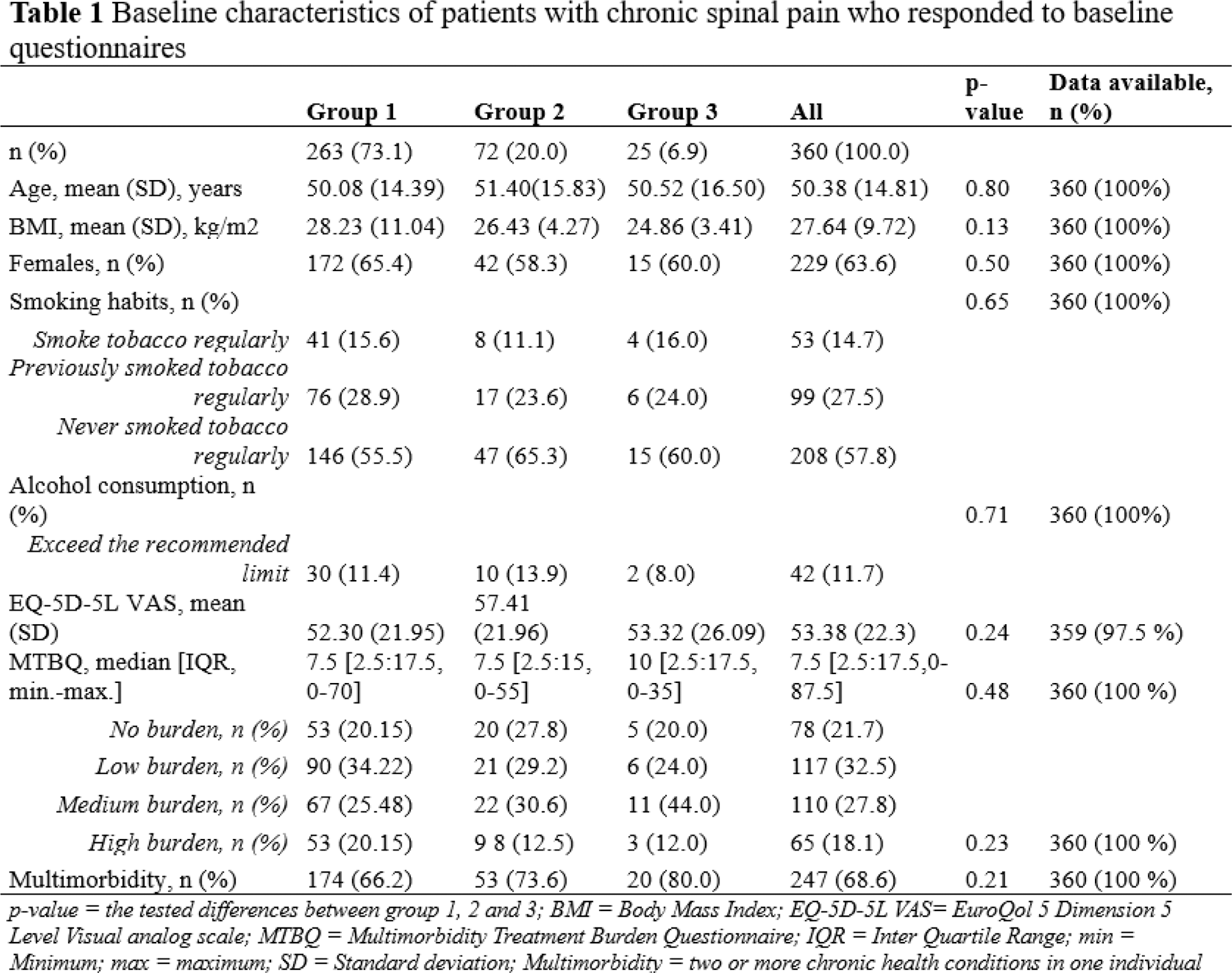

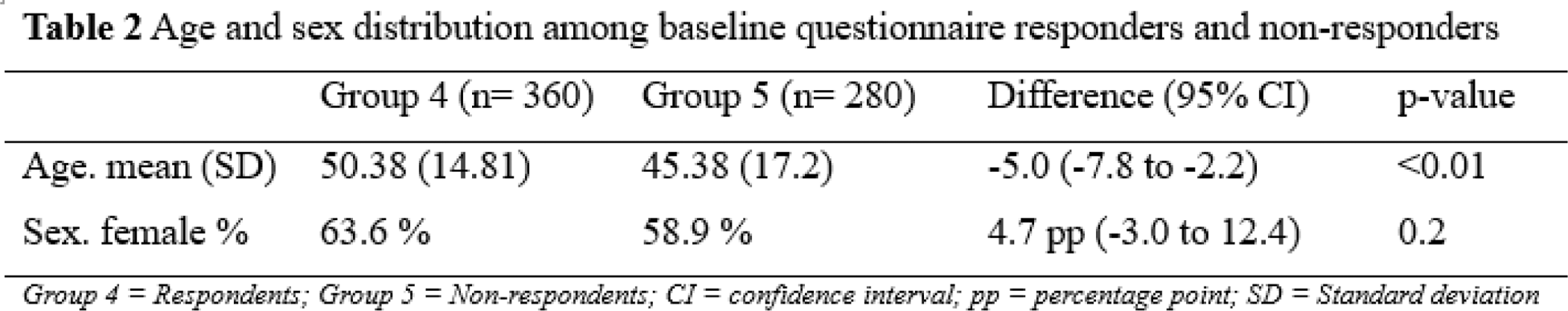

Methods: This prospective observational open-cohort study enrolled patients referred to Aalborg University Hospital for spinal pain from June 1, 2023 to April 1, 2024. Patient information was obtained from medical records and electronic questionnaires. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) were collected at baseline and at 3-month and 6-month follow-up. To investigate non-response bias using the successive wave analysis method, patients were categorized into groups based on their response patterns to the questionnaires: immediate responders (Group 1), those responding after one reminder (Group 2), those responding after two reminders (Group 3), all respondents (Group 4), and non -respondents (Group 5). Associations between response patterns and self-reported treatment burden (MTBQ), health-related quality of life (EQ-5D-5L), health status (EQ-5D-5L VAS), and the number of comorbidities were assessed at baseline, 3-month follow-up, and 6-month follow-up. The MTBQ is a 10-item measure of challenges in managing multimorbidity, including medication use and healthcare coordination [7], while EQ-5D-5L assesses five health dimensions on a 5-point scale, and EQ-5D-5L VAS rates overall health on a 100mm scale from 0 (worst) to 100 (best) [8]. Statistical analyses included one-way ANCOVA analyses and mixed regressions with repeated measures. Additionally, sex and age differences between respondents and non-respondents to the questionnaires were examined using chi-square test and independent samples t-tests.

Results: A total of 360 respondents and 280 non-respondents were included in the study. See Table 1 and Table 2. Among the respondents 68.6% met the criteria for multimorbidity, and nearly half of the respondents (45.9%) reported a medium to high treatment burden. One-way ANCOVA analyses revealed no significant differences between groups at baseline based on MTBQ, EQ-5D-5L, EQ-5D-5L VAS, or number of comorbidities. The mixed models of repeated measures revealed no significant differences over time in the outcomes. However, non-respondents were younger compared with the respondents, with a mean difference of 5 years (95% CI: -7.8 to -2.2, p-value: <0.01).

Conclusion: In Danish patients with chronic spinal pain, the self-reported treatment burden, health-related quality of life, health status, and the number of comorbidities did not appear to play a crucial role in their survey participation. However, younger age was associated with non-participation, suggesting that other factors among these younger patients might influence survey participation.

REFERENCES: [1] Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Aali A, Abate YH, Abbafati C, Abbastabar H, et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet. 2024 Apr;S0140673624007578.

[2] Hartvigsen J, Natvig B, Ferreira M. Is it all about a pain in the back? Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2013 Oct;27(5):613–23.

[3] Skou ST, Mair FS, Fortin M, Guthrie B, Nunes BP, Miranda JJ, et al. Multimorbidity. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022 Jul 14;8(1):48.

[4] He J, Morales DR, Guthrie B. Exclusion rates in randomized controlled trials of treatments for physical conditions: a systematic review. Trials. 2020 Dec;21(1):228.

[5] Gluud LL. Bias in Clinical Intervention Research. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2006 Mar 15;163(6):493–501.

[6] Phillips AW, Reddy S, Durning SJ. Improving response rates and evaluating nonresponse bias in surveys: AMEE Guide No. 102. Medical Teacher. 2016 Mar 3;38(3):217–28.

[7] Herdman, M., Gudex, C., Lloyd, A., Janssen, Mf., Kind, P., Parkin, D., Bonsel, G., & Badia, X. (2011). Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L).

Quality of Life Research

,

20

(10), 1727–1736.

[8] Duncan, P., Murphy, M., Man, M.-S., Chaplin, K., Gaunt, D., & Salisbury, C. (2020). Development and validation of the Multimorbidity Treatment Burden Questionnaire (MTBQ).

BMJ Open

,

8

(4), e019413.

Acknowledgements: NIL.

Disclosure of Interests: None declared.

© The Authors 2025. This abstract is an open access article published in Annals of Rheumatic Diseases under the CC BY-NC-ND license (