Background: VEXAS (Vacuoles, E1 enzyme, X-linked, Autoinflammatory, Somatic) syndrome is a rare and recently discovered adult-onset autoinflammatory disease affecting predominantly males. Main hematological manifestations at diagnosis encompass neutropenia, monocytopenia and monocytic dysfunction. Because of this and the extensive use of immunosuppressive treatments, patients with VEXAS present an increased risk of severe infectious episodes. These can also potentially trigger VEXAS flares, although the mechanisms underlying disease reactivation remain unclear.

Objectives: To investigate the prevalence of vaccination in VEXAS patients and to assess correlation between dosing, inflammatory flares and adverse reactions.

Methods: This retrospective study was conducted through an international survey disseminated between December 2024 and January 2025 across centers in Italy and Australia involved in the clinical management of patients affected by VEXAS. Demographic and clinical manifestations at diagnosis including sex, age and UBA1 mutation status were analyzed. Frequency of patients who underwent SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), Influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae and VZV (Varicella Zoster Virus) recombinant vaccinations and their related local and systemic adverse events were recorded. Additionally, VEXAS inflammatory flares after vaccinations administration were reported.

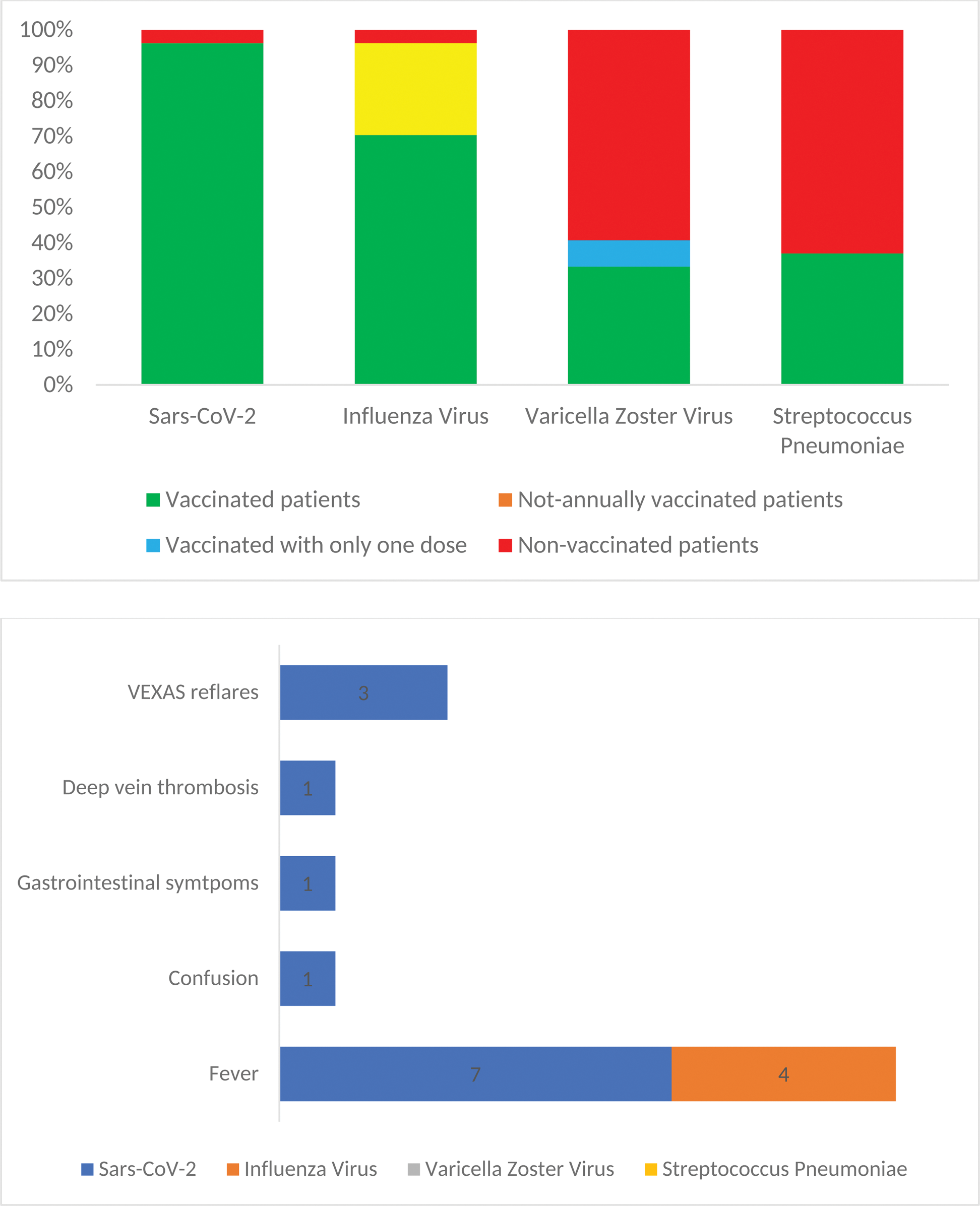

Results: Overall, 27 male VEXAS patients, all carrying pathogenic UBA1 mutations, were enrolled among 6 centers. The median age at diagnosis was 70 years (range, 55-86). Baseline features are summarized in Table 1. A total of 26 patients (96%) had received SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and, among these, 8 patients (32%) reported systemic adverse events. Specifically, 7 (26%) patients reported fever, 1 experienced altered mentation, 1 reported gastrointestinal symptoms, and 1 patient experienced deep vein thrombosis. Among our cohort, 19 patients (70%) received regular annual vaccination for Influenza virus. Only 1 patient (4%) never received Influenza vaccine. Considering those who received at least one dose of vaccine, 4 patients (15%) reported fever as a side effect. Regarding Streptococcus pneumoniae, 10 patients were vaccinated (27%), all of them with no reported side effects. Finally, as to VZV, 11 patients (41%) were given vaccination with the recombinant vaccine: of these, 9 (82%) completed the two doses schedule, while 2 (18%) received only one dose. None of these patients reported any adverse events. Regarding VEXAS syndrome flares, among those vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, 3 patients (11%) experienced disease reactivation with systemic symptoms: all presented fever, one patient also trigeminal neuralgia and another reported persistence arthralgias. Median daily glucocorticoid dose at vaccination in patients who had a VEXAS flare was 17.5 mg [0 – 20] of prednisone, which was not different compared to those vaccinated and who did not experience a flare: 7.5 mg [5 – 15], p=0.74. Concomitant immunosuppressive therapy in those having a disease reactivation included canakinumab and cyclosporine A for one patient, etanercept and methotrexate for the second one and canakinumab for the third one. Following vaccination-induced flares, the last patient required a change of immunosuppressive therapy, with reintroduction of cyclosporine A. Interestingly, all patients with a disease flare reported the same UBA1 mutation, Met41Val. None of the patients vaccinated for Influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae and VZV reported any disease reactivation following the vaccinations. A cartography of vaccinations and adverse events in VEXAS patients is showcased in Figure 1.

Conclusion: Our study is the first to focus on vaccination practices in patients with VEXAS syndrome. In our cohort, vaccinated patients received the anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in almost all cases and the influenza vaccine in more than 50% of cases. A more limited immunization coverage is applied to the recombinant anti-VZV and anti-S. pneumoniae vaccines, which would still be indicated in patients over 65 years of age (e.g., the age range of patients with VEXAS). In our cohort, only a minority of patients experienced vaccine-related adverse events or disease flares requiring treatment changes, confirming the safety of vaccinations in VEXAS. As such patients are more prone to developing infections, vaccinations are highly recommended. However, clinicians should be aware of their potential in stimulating inflammatory responses and a vigilant peri-vaccination evaluation is advisable.

Vaccination profiles in patients with VEXAS syndrome. Figure 1A: Vaccination by pathogen, specifically Sars-CoV-2, Influenza virus, Varicella Zoster virus, Streptococcus Pneumoniae. Figure 1B: Cases of adverse events reported after vaccinations.

Clinical features at diagnosis

| Clinical features | n=27 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Males, n (%) | 27 (100) |

| Age at Diagnosis | Median, years (range) | 70 (55-86) |

| UBA1 mutation | Met41Val, n (%)

| 11 (41)

|

| Clinical Manifestations at Diagnosis | Fever, n (%) | 14 (52) |

| Cutaneous involvement, n (%) | 15 (56) | |

| Pulmonary involvement, n (%) | 7 (26) | |

| Polichondritis, n (%) | 11 (41) | |

| Articular involvement, n (%) | 11 (41) | |

| Anemia, n (%) | 23 (85) | |

| Neutropenia, n (%) | 11 (41) | |

| Thrombocytopenia, n (%) | 11 (41) | |

| Deep vein thrombosis, n (%) | 5 (19) | |

| Ocular involvement, n (%) | 6 (22) | |

| Hematological condition | ICUS, n (%) | 9 (33) |

| CCUS, n (%) | 2 (7) | |

| MDS, n (%) | 14 (52) |

ICUS: Idiopathic Cytopenia of Undetermined Significance; CCUS: Clonal Cytopenia of Undetermined Significance; MDS: Myelodysplastic Syndrome

REFERENCES: NIL.

Acknowledgements: NIL.

Disclosure of Interests: None declared.

© The Authors 2025. This abstract is an open access article published in Annals of Rheumatic Diseases under the CC BY-NC-ND license (