Background: As recently reported in Cell Press journals, [1, 2] intestinal commensal purine-degrading obligate and facultative anaerobic gut microbiota in the human gut, comprise ~15-20% of human gut bacteria. These bacteria, predominantly of the Bacillota phylum, anaerobically degrade urate and multiple other purines, and convert urate to lactate, xanthine, and the anti-inflammatory short-chain fatty acids acetate and butyrate. Gut microbiota may partially compensate for uricase absence in humans [1, 2]. This enables homeostatic control over urate levels, particularly among those with chronic kidney disease (CKD) where, due to impaired renal elimination of urate, the majority of urate elimination occurs in the gut [3]. Since treatment with anaerobe-targeted antibiotics rapidly elevates serum and cecal urate in mice [1], and has been linked to increased incidence (relative to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (T/S) use) of the diagnosis of gout in a Stanford University cohort [1], we hypothesized that such antibiotic treatment in humans with CKD is linked to more frequent gout flares.

Objectives: To compare head-to-head the rate of gout flares among patients (stratified by CKD) treated with clindamycin, an antibiotic targeting both aerobic and anaerobic microbes, versus T/S, an antibiotic with limited anaerobic coverage.

Methods: We designed and conducted target trial emulations to compare clindamycin vs. T/S for the risk of gout flares, including separate target trials stratified by concomitant CKD. We used a general population database from January 1, 1997 to December 31, 2023, including all dispensed prescriptions. We included adults aged ≥18 years with dispensed prescriptions for ≥ 5 days of oral clindamycin or oral T/S, and no diagnosis of gout or receipt of antibiotics in the prior 12 months. Randomization was emulated based on >60 pre-exposure prognostic factors including sociodemographics, infection at baseline, comorbidities, medications, and healthcare utilization. Primary outcome was gout flare counts over three months after index date, ascertained by emergency department (ED), hospitalization, outpatient, and medication dispensing records [3]; gout flare rates were also determined over 12 months. To evaluate reproducibility and for spurious associations, we also assessed C. difficile infection as a positive control outcome (for which we expected clindamycin would be positively associated) and osteoarthritis (OA) encounter as a negative control outcome (for which we expected a null association). Poisson and Cox proportional hazards regressions were used to calculate adjusted rate ratios (RR) and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

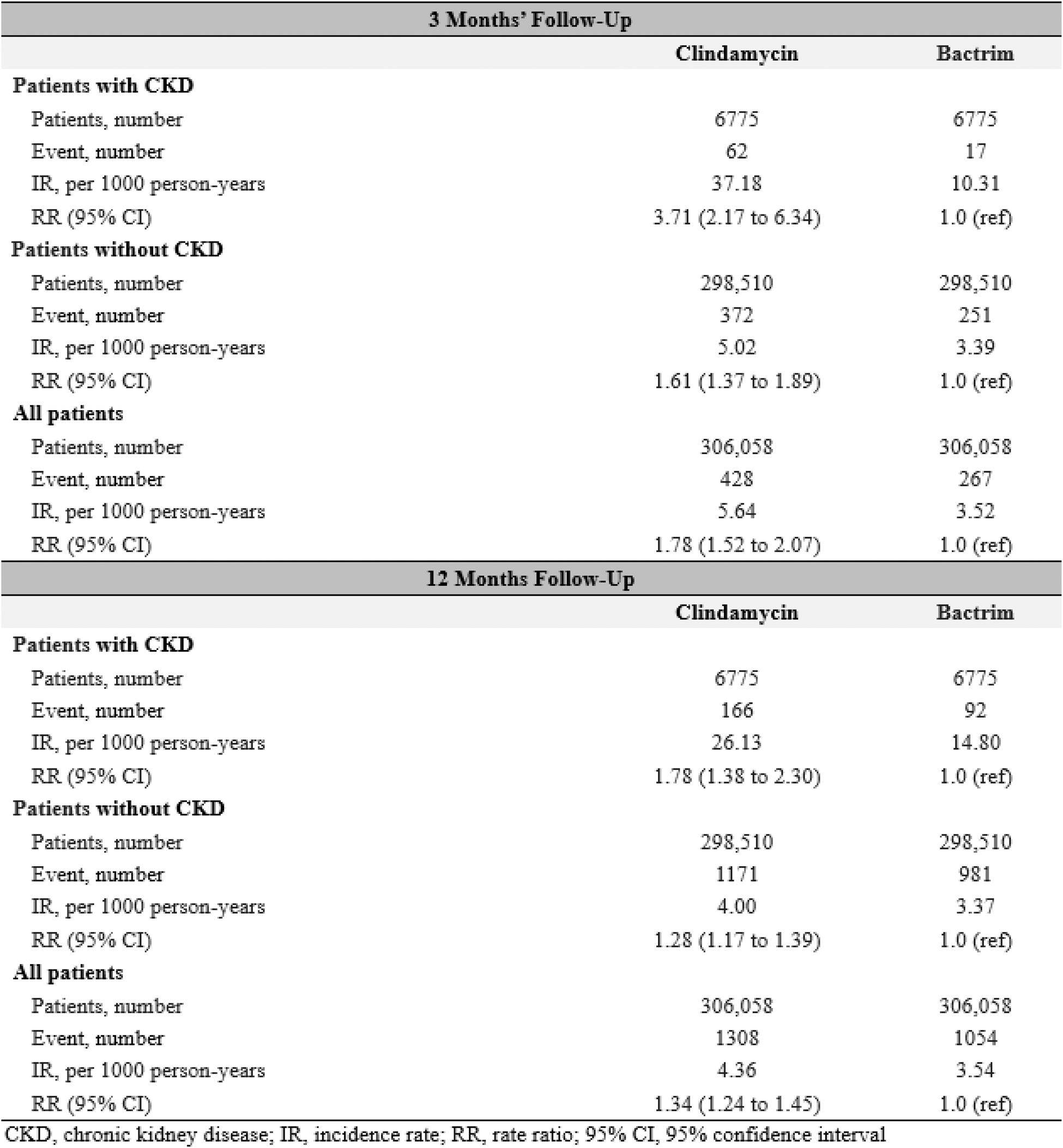

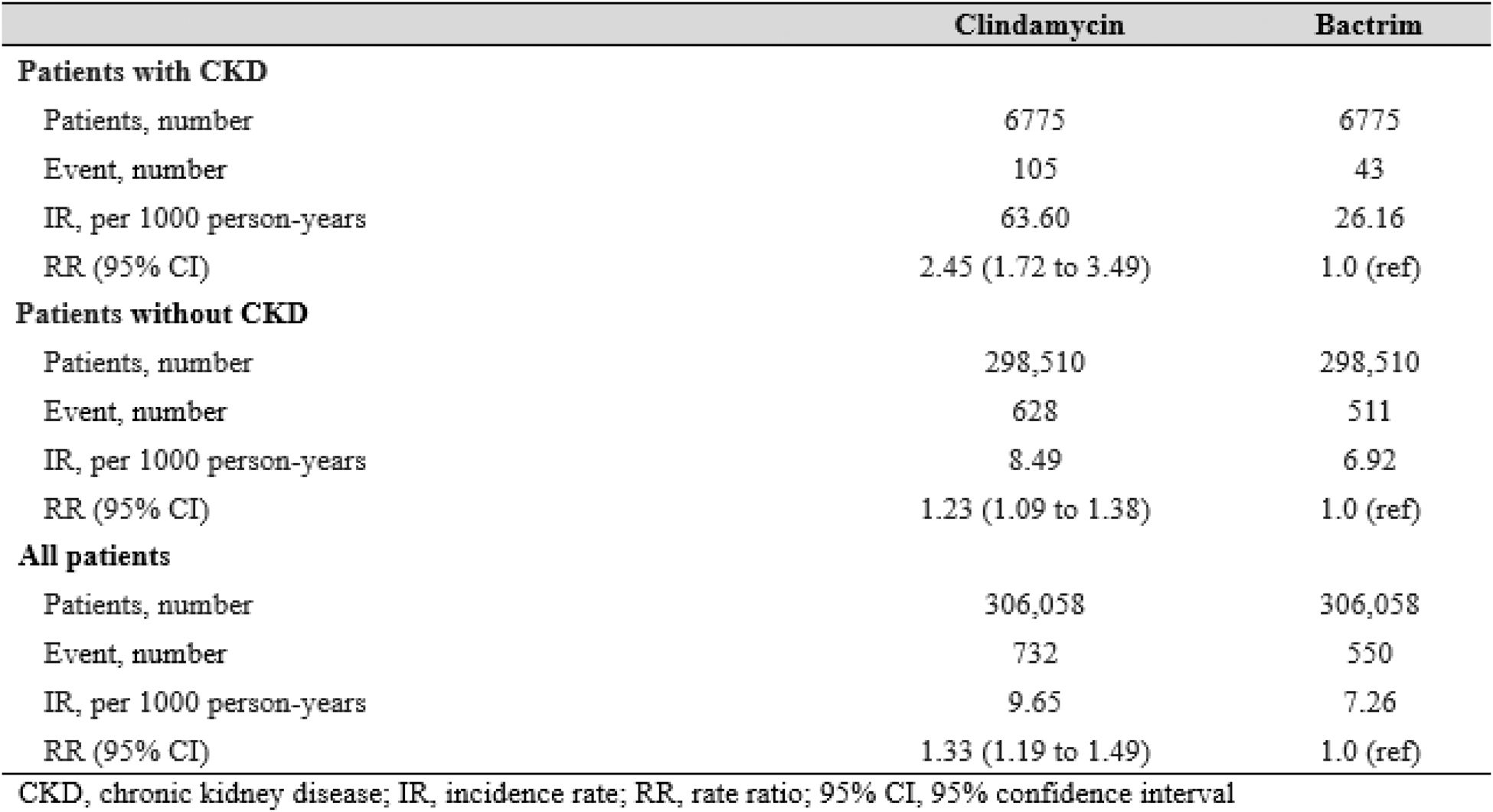

Results: After 1:1 propensity score matching, we included 306,058 adults initiating clindamycin and 306,058 initiating T/S (43% male, mean age 47 years). Baseline characteristics and prognostic factors (e.g., baseline infections, comorbidities, and medications) were well-balanced between the treatment arms (standardized differences <0.1 for all factors). Among the 13,550 propensity-matched individuals with CKD, rate of gout flares was higher among those initiating clindamycin vs. T/S (37.2 vs 10.3 per 1000 person-years, respectively), with an adjusted RR of 3.71 (95% CI: 2.17 to 6.34) (Table 1). These associations were smaller but remained significant among those without CKD, with an adjusted RR of 1.61 (1.37 to 1.89) (Table 1) (p-interaction, 0.003). Associations persisted when assessing gout flares for up to 12 months after index date (Table 1) and when comparing rates of all gout-primary encounters, regardless of medication dispensing (e.g., adjusted RR 2.45 [1.72 to 3.49] among those with CKD) (Table 2). In the control outcomes analysis, clindamycin initiators showed higher risk of C. difficile infection compared to Bactrim (adjusted HR 3.14 [2.02 to 4.90]), and no altered risk of OA encounter (adjusted HR 0.96, 0.85 to 1.08), both as expected.

Conclusion: In this general population study, treatment with an anaerobe-targeted antibiotic was associated with over three-fold higher rates of gout flares than treatment with the non-anaerobe-targeting antibiotic T/S, among those with CKD, accounting for baseline infections and other covariates. This effect modification by CKD status reflects the increased extrarenal urate burden experienced by the gut. These findings not only buttress a substantial role of gut purine-degrading bacteria (PDB) in urate disposition but also support suppression by gut PDB of gout inflammatory arthritis, particularly so with CKD, where the gut becomes the predominant site for urate elimination.

REFERENCES: [1] Liu et al., Cell 2023. PMID 37541197.

[2] Kasahara K, et al. Cell Host Microbe . 2023 PMID: 37279756.

[3] Terkeltaub and Dodd. Arthritis Rheumatol , In Press, 2025.

[4] McCormick et al., JAMA 2024. PMID 38319333.

Table 1. Recurrent gout flare count among patients with no history of gout at baseline, following initiation of Clindamycin versus Bactrim, after 1:1 propensity score matching.

Table 2. Frequency of gout-primary encounters among patients with no history of gout at baseline, following initiation of Clindamycin versus Bactrim, after 1:1 propensity score matching, 3 months’ follow-up.

Acknowledgements: NIL.

Disclosure of Interests: Natalie McCormick: None declared, Sharan Rai: None declared, Chio Yokose: None declared, Leo Lu: None declared, Robert Terkeltaub Synlogic, Atom Bioscience, Crystalys, Dyve Biosciences, Generate, and Convergence (all <$10,000), Lama Nazzal: None declared, Huilin Li: None declared, Dylan Dodd: None declared, Hyon Choi Ani, Protalix, Horizon, LG Chem, Shanton, Horizon, LG Chem.

© The Authors 2025. This abstract is an open access article published in Annals of Rheumatic Diseases under the CC BY-NC-ND license (