Background: Remote clinical management (remote assessment) advances the principle of offering the right care to the right patient in the right location. In this model, an electronic form is sent to a patient waiting to be reviewed and the response is assessed by a clinician; if the patient is judged to have active disease, a flare appointment is requested; otherwise a routine appointment is arranged. Although there is evidence that remote assessments accurately reflect disease activity in some rheumatic diseases (Malley et al., 2021; Soni et al., 2022; Kurzeja et al., 2023), data on systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is lacking.

Objectives: We aimed to evaluate the outcomes of remote assessment in patients with SLE by comparing remote assessment with subsequent in-person assessment. We audited the effectiveness of this process in terms of correctly identifying patients with active SLE, who require treatment change. We also wanted to compare patients who were defined as stable, using remote assessment, with their subsequent clinical outcome in the following 4 to 12 months.

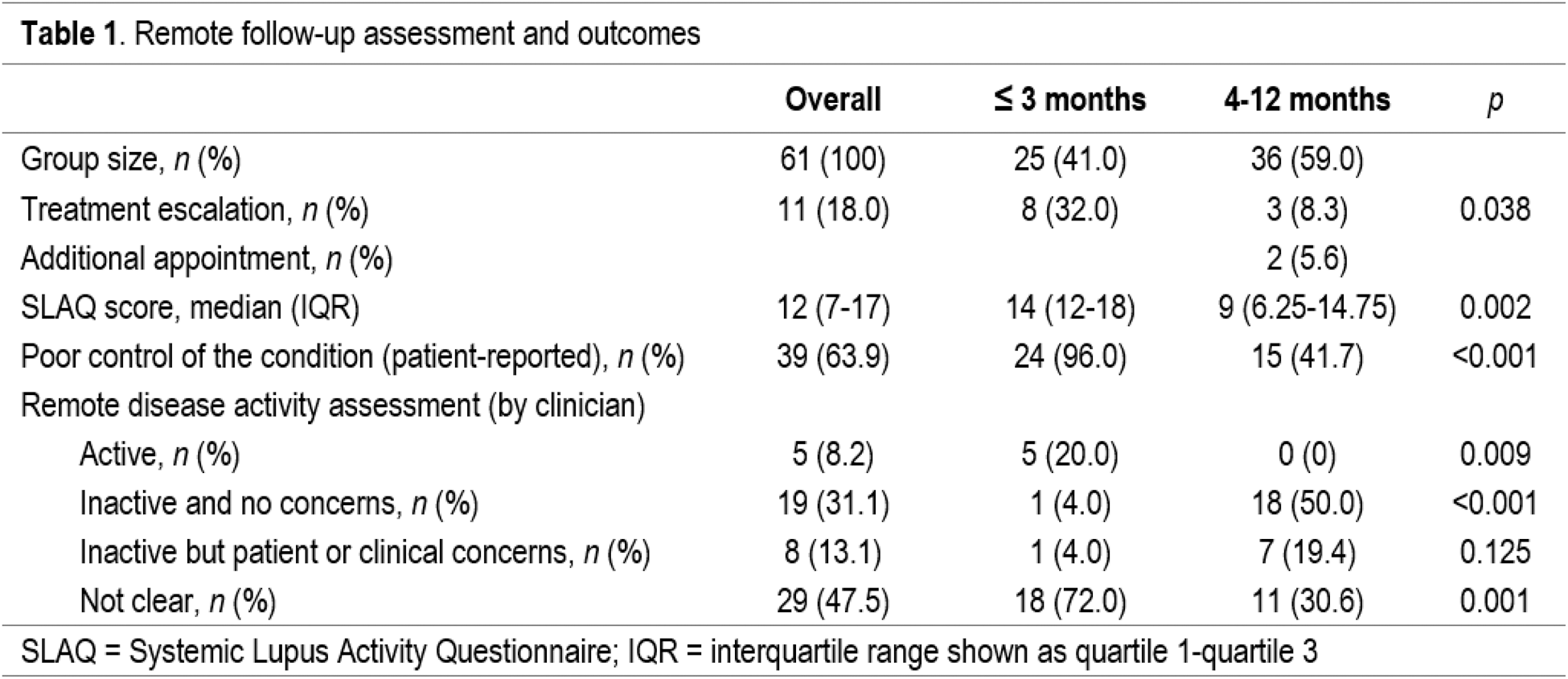

Methods: All remote assessments of patients with SLE conducted between January 2020 and September 2023 were eligible for inclusion; forms completed by the same patient at different times were included. The electronic questionnaire includes patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) of disease activity (Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire, SLAQ), health-related quality of life (SF-36), a description of the overall control of the condition and free text boxes to document any other issues. After reviewing the form, an appointment is requested within three months for patients who may be flaring or experiencing problems with medication (“unstable” group). By contrast, patients in remission or partial remission are offered a follow-up consultation in 4 to 12 months (“stable” group). Only face-to-face (F2F) appointments were included in our analysis. The proportion of patients requiring treatment intensification at the F2F appointment was compared between both groups (stable and unstable). We also recorded the number of patients requiring an additional consultation before the next scheduled visit, within the stable group. As a secondary analysis, SLAQ score, patient-reported and clinician-reported control of the condition were compared between both groups and contrasted with the need for a change in treatment. Sensitivity, specificity and predictive values were calculated for a cut-off of ≥9 points in SLAQ score (as described in the original publication). Questionnaire responses and clinician’s decision on follow-up were retrieved from our in-house database. Requirement for treatment escalation in the follow-up consultation was obtained from two clinician-recorded encounter forms and electronic patient records.

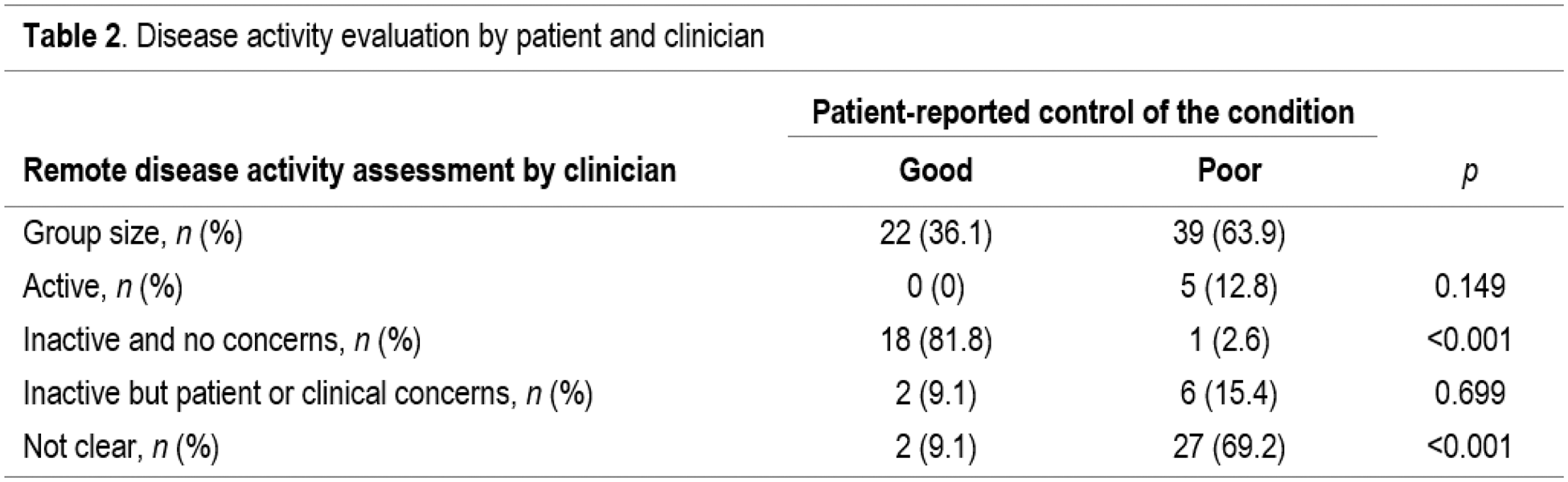

Results: Of the 61 patients included in the audit, 25 (41.0%) were assessed as being unstable (requiring an in-person appointment within three months; Table 1). Eight of them (32.0%) required treatment intensification due to disease activity, while only 3/36 patients (8.3%) considered stable required any pharmacological adjustment ( p =0.038). Among patients remotely evaluated as stable, only two (5.6%) required an additional visit prior to the scheduled appointment, but none of them had their treatment modified. Patients judged as unstable showed a median SLAQ score five points higher than patients deemed stable ( p =0.002). Overall, 63.9% of patients reported poor disease control (96.0% in unstable group vs 41.7% in stable group, p <0.001). However, clinicians felt that only 8.2% of patients had active disease based on information in remote assessment forms, and all of them were reviewed within three months ( p =0.009). The majority of patients considered inactive were seen within 4 to 12 months, regardless of the presence of patients’ or physicians’ concerns. Disease activity status was uncertain in almost half of the whole cohort (47.5%), and the majority of these cases were scheduled for assessment within three months ( p =0.001). Comparison of disease activity assessment between patients and clinicians is displayed in Table 2. When patients reported that the condition was under control, doctors’ evaluation concurred in 90.9% of the cases. By contrast, activity status was considered uncertain in almost 70% of cases when patients reported poor control of the disease. Regarding the need for therapy intensification, 10/39 patients (25.6%) reporting poor control of the condition required an adjustment, while this happened in only 1/22 patients (4.5%) reporting good disease control ( p =0.045); this difference was not observed if we use doctor’s remote evaluation on disease activity as a reference (20.0% vs 7.4%, p =0.410) [data not shown]. A cut-off of ≥9 points in SLAQ score had a sensitivity of 81.8%, specificity of 32.0%, positive predictive value of 20.9%, and negative predictive value of 88.9% to predict an increase in immunosuppression at the F2F appointment.

Conclusion: The use of remote asynchronous electronic forms is a reliable method for assessing disease activity. Clinician remote evaluation predicts stable disease, and it effectively identifies patients who may need an early review to consider adjusting treatment. However, form assessment cannot clearly determine whether the disease is active or not. SLAQ score alone has limited predictive value for treatment escalation. Remote management has an important role in offering safe, convenient and efficient care to patients.

REFERENCES: NIL.

Acknowledgements: Aguilar-Coll M. received a grant from Fundación Española de Reumatología (FER) to do a clinical observership in the Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre.

Disclosure of Interests: None declared.

© The Authors 2025. This abstract is an open access article published in Annals of Rheumatic Diseases under the CC BY-NC-ND license (