Background: Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) and Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF) are the most common autoimmune and autoinflammatory rheumatic diseases in childhood, respectively [1, 2]. Problems such as joint pain, muscle weakness, decreased aerobic capacity, and fatigue in children and adolescents with arthritis may lead to low levels of physical fitness [3]. Physical fitness is an important determinant of health-related outcomes, and its testing in youth can be used as a surveillance tool to obtain a proxy measure of child/adolescent health status. The FitnessGram Physical Activity Test Battery is a validated and reliable assessment tool developed by the Cooper Institute to evaluate health-related physical fitness in children and adolescents. Fitnessgram’s use in physical fitness monitoring for youth can provide information about patterns in fitness attainment across subgroups and over time, which in turn informs physical activity programming and exercise interventions [4].

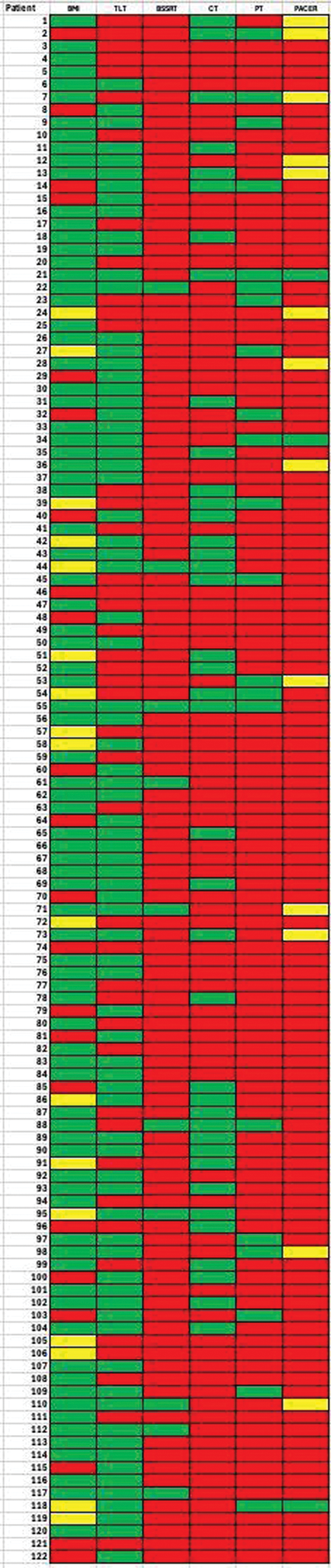

Objectives: The aim of this study was to evaluate the physical fitness levels of children and adolescents diagnosed with JIA and FMF using the FitnessGram Physical Activity Test Battery and to roadmap their physical fitness profiles using traffic light colors.

Methods: A total of 131 children and adolescents, including 93 (63 girls, 30 boys) diagnosed with JIA and 38 (19 girls, 19 boys) with FMF, aged between 10 and 18, were included in the study. The physical fitness levels of the patients were assessed using the Curl Up Test (CT), Push-up Test (PT), Trunk Lift Test (TLT), Back-Saver Sit-and-Reach Test (BSSRT), and the Progressive Aerobic Cardiovascular Endurance Run Test (PACER), which are part of the FitnessGram Physical Activity Test Battery. Height and weight were measured, and Body Mass Index was calculated. The results obtained from the physical fitness tests were compared with the FitnessGram Health Category Standards, which are determined by gender and age groups for each patient. Based on the test results, patients were classified as Healthy Fitness Zone (HFZ), Needs Improvement (NI), or Needs Improvement- Health Risk for each health category.

Results: The mean ages of the children and adolescents diagnosed with JIA and FMF included in the study were 14.07 ± 1.98 and 13.81 ± 2.19, respectively. When the FitnessGram standards were applied for JIA patients, %68.8 of them were categorized in the NI-Health Risk and %31.2 of them in the HFZ for Curl-up test, %82.8 of them in the NI-Health Risk and %17.2 of them in the HFZ for Push-up test, %37.6 of them in the NI-Health Risk and %62.4 of them in the HFZ for Trunk lift test, %93.3 of them in the NI-Health Risk and %6.7 of them in the HFZ for BSSRT, %85.2 of them in the NI-Health Risk, %12.4 of them in the NI and %2.5 of them in the HFZ for PACER, %18.5 of them in the NI-Health Risk, %12.0 of them in the NI and %69.6 of them in the HFZ for BMI. When the FitnessGram standards were applied for FMF patients, %65.8 of them were categorized in the NI-Health Risk and %34.2 of them in the HFZ for Curl-up test, %84.2 of them in the NI-Health Risk and %15.8 of them in the HFZ for Push-up test, %31.6 of them in the NI-Health Risk and %68.4 of them in the HFZ for Trunk lift test, %86.8 of them in the NI-Health Risk and %13.2 of them in the HFZ for BSSRT, %92.1 of them in the NI-Health Risk, %5.3 of them in the NI and %2.6 of them in the HFZ for PACER, %18.4 of them in the NI-Health Risk, %18.4 of them in the NI and %63.2 of them in the HFZ for BMI. The results and the categorisation of the physical fitness tests for patients diagnosed with JIA and FMF are shown in Table 1. All the test results of children and adolescents with JIA and FMF were statistically similar (p>0.05) and the scores of nearly all participants were lower than the age appropriate normal scores.

Conclusion: The results of this study showed that almost all children and adolescents diagnosed with JIA and FMF were categorized as at risk in terms of flexibility, upper extremity and abdominal muscle strength and endurance, and cardiorespiratory fitness on the physical fitness roadmap. Specifically, more than 80% of the participants in both groups fell into the NI-Health Risk category for tests assessing aerobic fitness and upper body strength, highlighting these as critical areas of concern in JIA and FMF. While abdominal strength and flexibility also showed significant deficits, a relatively higher percentage of participants achieved the Healthy Fitness Zone in these parameters, suggesting some variability in fitness limitations. The FitnessGram physical fitness roadmap provided guidance in identifying the issues present in patients with JIA and FMF. The use of a traffic light colors in this mapping approach proved highly advantageous, offering an intuitive and visually clear way to categorize physical fitness levels. This method not only facilitated the understanding of fitness deficits but also allowed clinicians and researchers to quickly identify critical areas requiring immediate intervention. When designing exercise programs for patients with JIA and FMF, we believe that focusing on these parameters will facilitate the clinical decision-making process and be beneficial in developing individualized exercise programs.

REFERENCES: [1] Ravelli, Martini. 2007. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The Lancet.

[2] Ozdogan, Ugurlu. 2019. Familial mediterranean fever. La Presse Médicale.

[3] Houghton 2012. Physical activity, physical fitness, and exercise therapy in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The Physician and Sportsmedicine.

[4] Day et al. 2023. NYC FITNESSGRAM: population-level physical fitness surveillance for New York City youth. American Journal of Epidemiology.

Physical fitness roadmap

Acknowledgements: NIL.

Disclosure of Interests: None declared.

© The Authors 2025. This abstract is an open access article published in Annals of Rheumatic Diseases under the CC BY-NC-ND license (