Background: Still’s disease is a multisystem autoinflammatory disease with heterogeneous clinical features. In the EULAR/PReS recommendations published in 2024, IL-1 or an IL-6 inhibitor should be started as early as possible after diagnosis [1]. CID is defined in this recommendation as the absence of Still’s disease related symptoms and normal ESR or CRP and is one of the intermediate goals to achieve the ultimate goal (drug-free remission) [1]. In Japan, IL-6 inhibitors are now commonly used for induction treatment of Still’s disease. However, MAS is frequently reported in Still’s disease, and TCZ (tocilizumab) is also thought to be one of the causes of MAS in Still’s disease [2]. In order to achieve CID with glucocorticoids less than 0.1 or 0.2 mg/kg/day at 3 months, one of the intermediate goals proposed in this recommendation, induction of TCZ as early as possible while avoiding the development of TCZ-MAS (MAS developing after TCZ induction) is essential. However, there is little evidence of laboratory markers to guide the ideal timing of TCZ induction.

Objectives: To determine prognostic factors for the development of MAS and the safety and efficacy of TCZ as an induction treatment for Still’s disease. To determine the optimal timing of initiation of TCZ in Still’s disease.

Methods: We conducted a single-centre retrospective study of patients with Still’s disease diagnosed or treated at Kurashiki Central Hospital (Kurashiki, Japan) between January 2004 and October 2024. Definitive diagnosis of Still’s disease was made according to the Yamaguchi criteria. Clinical and laboratory data, including serum IL-6, IL-18 levels, clinical courses such as CID achievement at week 1, month 3, MAS development, were collected retrospectively. We evaluated the efficacy of treatment by comparing the achievement of CID at month 1 and month 3 between the TCZ group (those who continued TCZ for more than 3 months as induction treatment for Still’s disease) and the non-TCZ group. We also compared the TCZ-MAS group (those who developed MAS after TCZ induction) with the TCZ group (non-MAS group) to determine the prognostic factor for the development of TCZ-MAS.

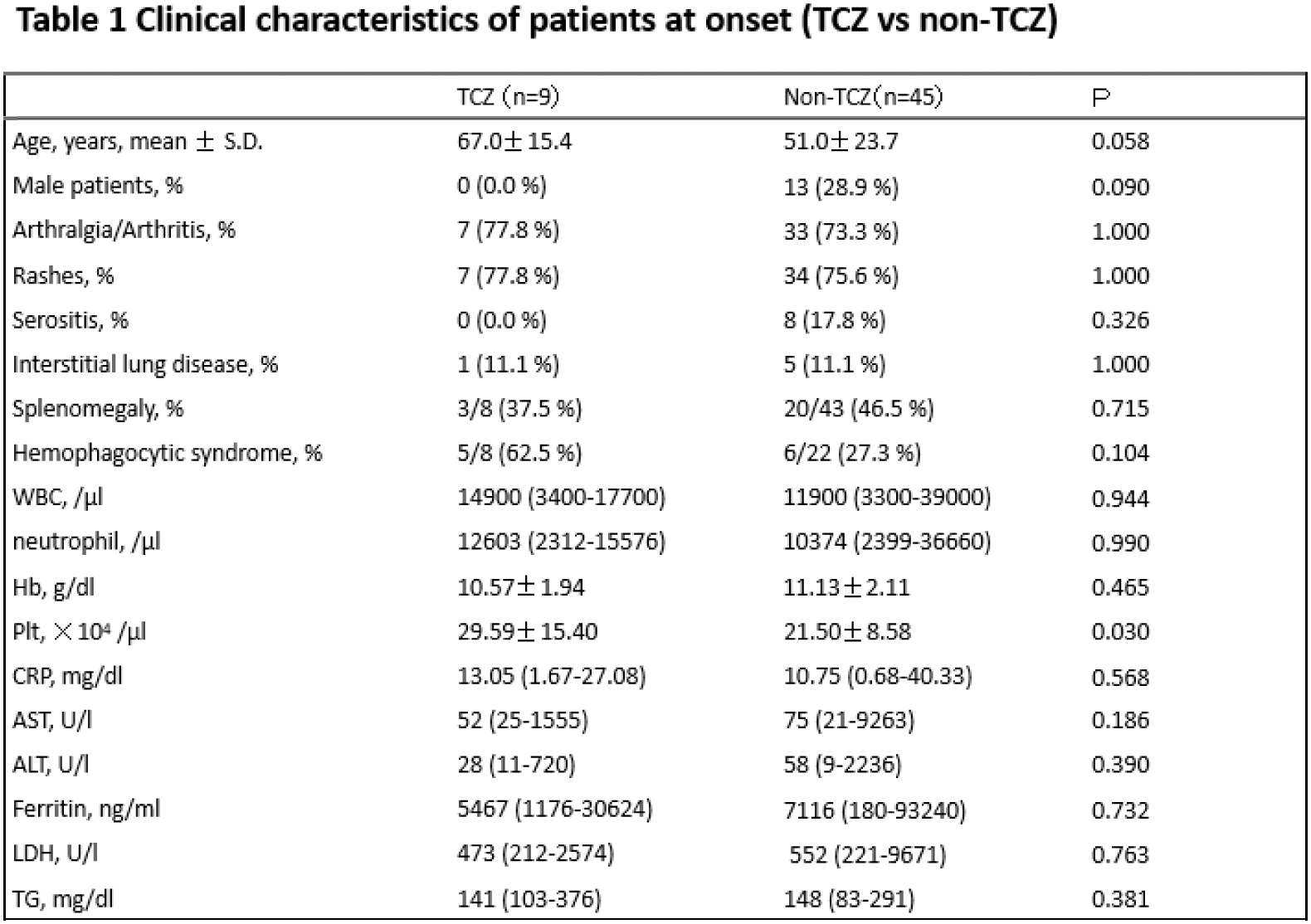

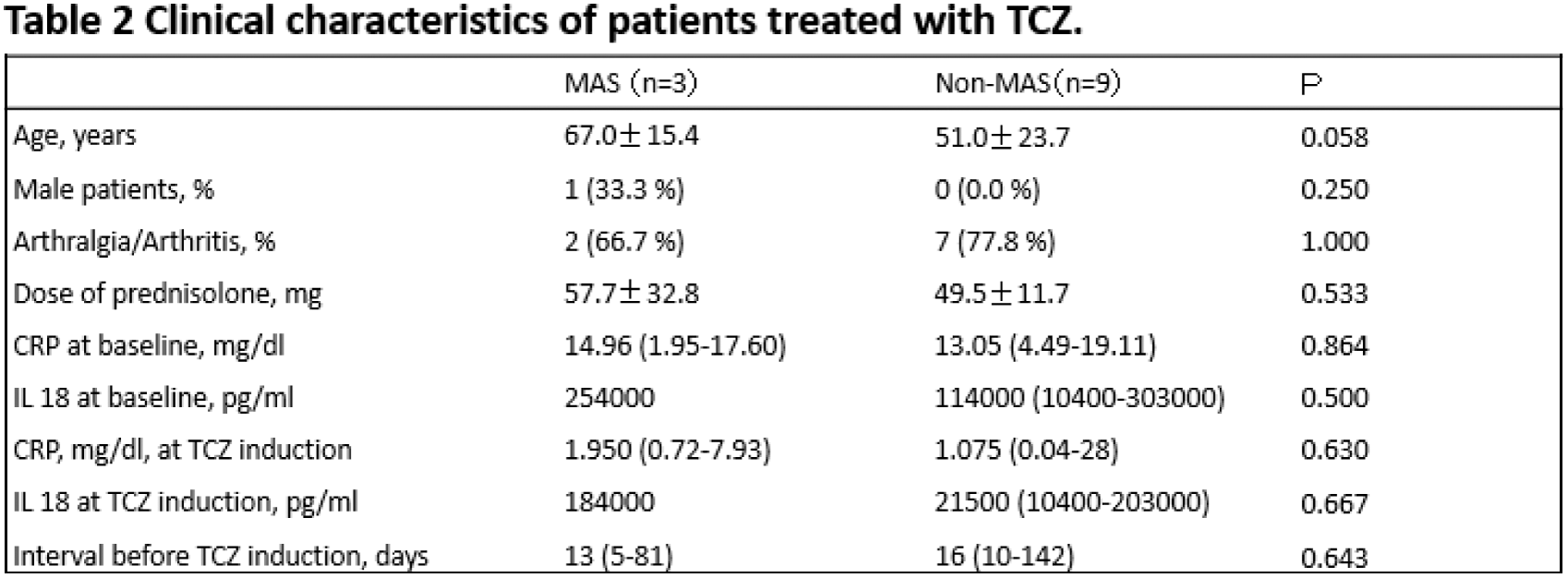

Results: Of the 69 AOSD patients enrolled in this study, 2 patients had paediatric disease onset. TCZ was used as induction treatment in 13 patients, of whom 3 were unable to continue TCZ due to the development of MAS or elevation of liver enzymes. In contrast, none of the patients who received TCZ as a reinduction treatment or after remission developed MAS. Fifty-four patients with available clinical information at baseline, week 1 and month 3 were evaluated (age 54.4 ± 22.5 years, male sex 24.1%). As shown in Table 1, clinical characteristics were similar between the TCZ and non-TCZ groups. Median CRP levels at month 3 were significantly lower in the TCZ group than in the non-TCZ group. (0.015 versus 0.070, P=0.013) On the other hand, we could not find a significant difference in the mean dose of prednisolone at month 3 between the TCZ group and the non-TCZ group (16.07±6.43 versus 20.18±10.88). As shown in Table 2, the baseline clinical characteristics at TCZ induction, such as baseline CRP levels, dose of prednisolone and time after prednisolone induction, were similar between the TCZ-MAS group and the non-MAS group. However, CRP levels at week 1 and the CRP ratio (CRP at week 1/CRP at baseline) were significantly higher in the TCZ-MAS group than in the non-MAS group (0.44 versus 9.27, P=0.042) and (0.068 versus 0.75, P=0.009), respectively. We also observed changes in IL-18 levels, which decreased with the initiation of TCZ iv and the switch to TCZ sc treatment.

Conclusion: TCZ was useful as an induction treatment in Stiill’s disease, making it more feasible to achieve CID at 3 months; reducing the levels of CRP. On the other hand, we could not show a significant difference in the dose of predonisolone at month 3, suggesting that earlier induction of TCZ is essential, as some of our patients took more than one month to start TCZ treatment. CRP levels at week 1, CRP ratio (CRP at week 1/CRP at baseline) levels were useful in predicting TCZ-MAS in our patients and this means that using laboratory data to optimise the timing of TCZ induction is essential to prevent TCZ-MAS as well as achieving CID at 3 months and reducing the dose of glucocorticoids. IL-18 levels may also have something to do with the development of MAS and may guide our treatment plan, but we need more research to show this.

REFERENCES: [1] Bruno Fautrel. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024 Nov 14;83(12):1614-1627.

[2] Toru Yamabe. Mod Rheumatol. 2022 Jan 5;32(1):169-176.

Acknowledgements: NIL.

Disclosure of Interests: None declared.

© The Authors 2025. This abstract is an open access article published in Annals of Rheumatic Diseases under the CC BY-NC-ND license (